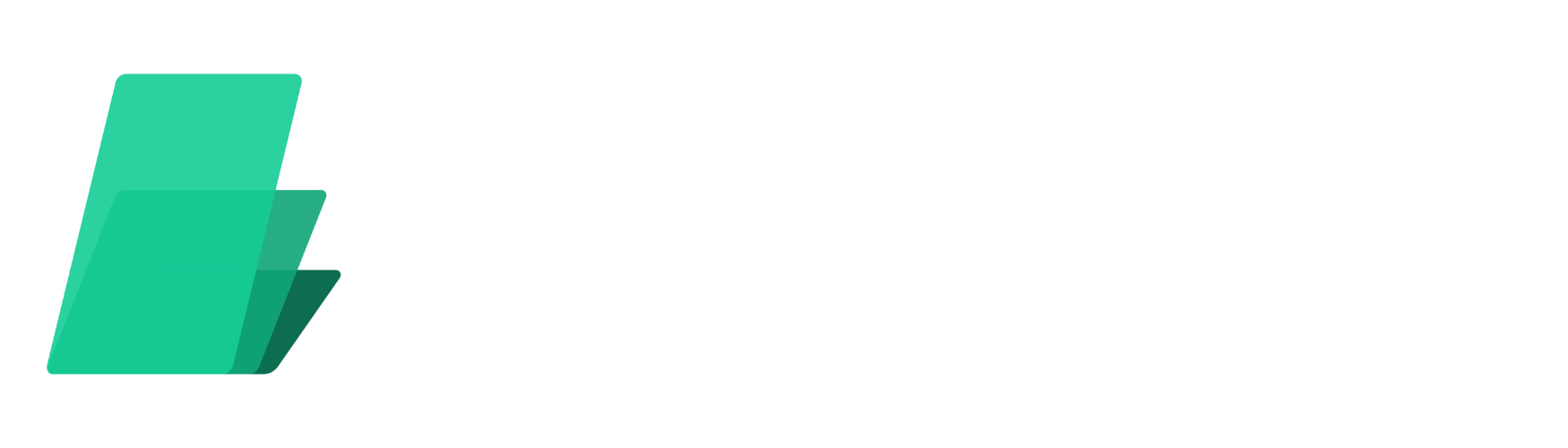

The Leadership Fallacy

Leadership is often treated as a timeless, universal quality. We celebrate bold, engaging CEOs and assume their past successes will translate into future victories – regardless of the context. Yet, the real-world failure of many high-profile executives reveals a fundamental truth: leadership cannot be assessed in isolation. Even highly regarded leaders can struggle and fall when placed in the wrong situation.

In reality, leadership effectiveness is not a fixed trait – it depends on a range of underlying skills, the impact of which is highly contingent on the circumstances. The industry, the team, the culture, and the prevailing challenges all shape whether a leader will thrive or fail. This article explores why the situation is the missing piece in leadership assessment.

The Myth of the Universal Leader

When we think of major organisational successes – whether achieving double-digit growth, delivering a major project, or leading a turnaround – we often attribute the lion’s share of the victory to a single person: the leader. Our cognitive shorthand tells us that their vision, expertise, and ability to mobilise people were the key drivers of success. Since these qualities are seen as part of the leader, we assume they will succeed in other contexts too. After all, leadership skills are portable, so they should be able to do it again elsewhere, right?

However, data on leader failure tells a different story. In the FTSE 100, at least 10% of newly appointed CEOs fail within their first two years (Russell Reynolds, 2024). Other sources suggest a higher failure rate, with 30% to 50% of new executives failing in their first 18 months (Forbes, 2020). Crucially, the cause is often a misalignment between the leader’s style or skills and the demands of the new role.

While executive-level exits are highly visible, leadership misalignment occurs at all levels, from supervisor to C-suite minus 1. Even those initially deemed highly promising may fail to meet expectations once in post. Though their exits are often handled discreetly, the underlying issue is the same: they couldn’t adapt their leadership approach to the situational demands.

Why Situational Factors Matter

What causes this gap between leadership expectations and reality? Too often, the way leaders are assessed overlook vital situational . While we may hire external candidates from the same or similar industry sectors, we often fail to consider the specific business conditions, cultural context, and role requirements.

The same leadership qualities that drive innovation in a tech start-up may fall flat once the company is acquired by an established enterprise focused on stability. Similarly, a cost-efficiency expert may excel during a financial downturn but struggle to lead an organisation through aggressive expansion. Promotion to a higher level in the same discipline or a sideways move into a different type of role can alter the leadership demands, requiring previously underutilised skills.

To accurately assess leadership, we need to move beyond the myth of the universally effective leader. A leader’s impact is significantly affected by key situational factors, such as hierarchical level, industry-specific demands, business trajectory, strategy, organisational culture, and the qualities of team members. Leaders cannot simply ‘plug and play’ as they move into new roles.

When the Situation is Ignored: Leadership Failures in the Real World

Aside from the exit rates of underperforming leaders, real-world examples highlight the consequences of ignoring the situation. Consider three high-profile cases: the 2008 financial crisis, Boeing’s 737 Max disaster, and the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

In the 2008 financial crash, CEOs with aggressive growth mindsets pursued high-risk subprime lending strategies. When the financial context shifted, their strategies collapsed. In the UK, the collapse of Northern Rock and Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) demonstrated how appointing leaders without the necessary financial expertise contributed to reckless decision-making. Leadership failure was not simply about personal incompetence or risk appetite but a glaring mismatch between leadership skills and the demands of a volatile financial landscape.

A decade later, Boeing’s 737 Max crisis revealed similar leadership blind spots. After two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019, CEO Dave Calhoun was widely criticised for prioritising shareholder interests over safety. Boeing’s leadership failed to address systemic safety issues, focusing instead on financial recovery. In this highly technical and safety-driven industry, leadership required engineering oversight and regulatory credibility – qualities that Boeing’s leaders apparently failed to prioritise.

More recently, the Post Office Horizon IT scandal became one of the UK’s biggest miscarriages of justice. Faulty technology, corporate negligence, and systemic injustice led to the wrongful prosecution and suffering of hundreds of innocent people, including financial ruin, imprisonment, and several suicides. The Post Office’s leaders clung to a corporate defensiveness strategy, failing to recognise the growing public and political outcry. Their inability to adapt to the evolving situation demonstrated a catastrophic disconnect from the human and reputational cost of their .

Leading for the Situation: One Size Does Not Fit All

These case studies underscore the reality that leadership is situational. This principle is not only demonstrated in real-world failures but also supported by decades of empirical research with controlled studies.

In the 1950s and 60s, leadership scholars debated whether task-focused or people-focused strategies were more effective. Eventually, they concluded that the success of either approach depended on the situation (Bass, 1981).

Later research compared participants’ intelligence and experience when performing leadership tasks. In stressful conditions, experience predicted leadership effectiveness, while intelligence prevailed in low-stress situations (Fiedler, 1995). The ability to read the situation and adapt strategies was key to success.

Situational factors also include the team itself. The capabilities, attitudes, and coordination of direct reports, as well as cross-team collaboration, all influence leadership effectiveness (Yukl & Gardner, 2020). Furthermore, leadership effectiveness is not absolute – it is a label ascribed by observers, whose judgments are shaped by their own perspective. For example, a leader admired by shareholders for driving profits may simultaneously be viewed as ineffective by employees for neglecting workplace morale (Tsui et al., 1995).

Organisational culture is another crucial situational factor. Quinn and Rohrbaugh’s (1983) Competing Values Framework identifies four dominant value orientations, which refer to innovation, stability, teamwork, and results. Their research shows that organisations often experience tension between competing demands, such as flexibility versus stability. Leaders who recognise and align their style with the dominant values of their organisation are more likely to succeed.

Rethinking Leadership Assessment

Whether based on case studies, research studies, or first-hand organisational experience, the conclusion is clear: leadership is situational, not universal. A leader’s success depends on their ability to read and adapt to the situation. There is no ‘one best way’ to lead – thank goodness, we can be authentic! – but situational awareness is critical.

So, what does this mean for leadership assessment? Rather than focusing exclusively on the leader’s qualities, organisations must incorporate key situational elements. Variables such as role type, hierarchical level, and organisational culture should be integral to leadership assessments and feedback. By considering context, organisations can better predict how leaders will thrive – or struggle – as the situation changes.

Leadership effectiveness is not a static quality – it is shaped by the interplay of individual characteristics and situational demands. The failure of once-celebrated executives, as well leaders in the engine room of organisations, reveals the cost of assessing leadership in isolation. Only by considering the situation as we evaluate leaders can we fully understand their capacity and how to focus their development for success.

What’s Your View?

We’d love to hear from you:

- Have you seen leaders rise and fall as the situation changes?

- Does your organisation include situational measures when assessing leaders? If so, what methods work best?

Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

In the coming weeks, we will continue to explore leadership development methodologies and propose new approaches for assessing and enhancing the capability of current and future leaders across industries.

References

Bass, B.M. (1981). Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research. Theory, research, and managerial applications. New York: Free Press.

Fiedler, F.E. (1995). Cognitive resources and leadership performance. Applied psychology, 44(1), pp.5-28.

Forbes (March 13, 2020). Why Most New Executives Fail – And Four Things Companies Can Do About It. Article by M. Ettore. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescoachescouncil/2020/03/13/why-most-new-executives-fail-and-four-things-companies-can-do-about-it/

Quinn, R.E. and Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management science, 29(3), pp.363-377.

Russell Reynolds (April 2, 2024). FTSE 100 CEO appointments reach five-year high as one in ten CEO appointments fail within two years. https://www.russellreynolds.com/en/about/newsroom/ftse-100-ceo-appointments-reach-five-year-high

Tsui, A.S., Ashford, S.J., Clair, L.S. & Xin, K.R. (1995). Dealing with discrepant expectations: Response strategies and managerial effectiveness. Academy of Management journal, 38(6), pp.1515-1543.

Yukl, G.A. & Gardner, W.L. III (2020). Leadership in organizations. 9th edn. Harlow: Pearson.